Dorotheenstadt Cemetery, Berlin

Dorotheenstadt Cemetery, Berlin, July 2023

Digital Pinhole PhotographyA Pilgrimage at Minidoka, July 7 2023

This morning during the opening plenary session of the Minidoka Pilgrimage, a lone moth flickers around the auditorium. Tonight a cloud of them dances the bon odori on the banks of the canal across from the land where Block 8, Barrack 2, Room C once stood.

Return to Pictorialism: Naturalism, Artifice, Chance

I revisit digital pinhole photography, beginning with some studies to re-familiarize myself with the technology. A day trip to St. Louis means 12, uninterrupted hours of varied shooting conditions.

Heart Mountain Pilgrimage, July 30 2022

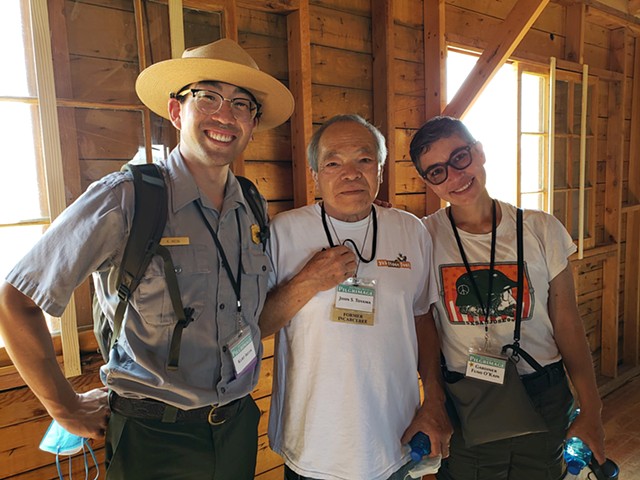

This weekend I have had the honor and privilege of meeting people who experienced this camp firsthand. John Toyama was born at Heart Mountain. He generously shared his story with me and Ranger Kurt Ikeda. The opportunity to hear John tell his own stories and to reflect on the hardships that his parents endured in order to make life bearable for their children, and to hear these oral histories told in the location where they took place, is something I will never forget.

Diversity Within a Microcosm: Varieties of Expression in Japanese American Art

Gardiner’s tarpaper sculpture, titled Silence (Father, Mother, Sister, Brother) is part of this exhibition.

Curated by Alice Murata

May 21-August 15, 2022

Northeastern Illinois University (NEIU) Ronald Williams Library

5500 N St Louis Ave

Chicago, IL 60625Diversity in a Microcosm is “an opportunity to experience artwork by Chicagoans of Japanese descent across generations. Although all the artists share traits based on blood, culture and history, the ways they have expressed themselves is a study in diversity.”

—Alice MurataWorking Title: Koi for The Unaccompanied Video Release

The last days of summer are spent on the road between Crystal City and Carrizo Springs, making connections literal and metaphorical between the history and present of those places.

This one is for my father, who can tell you first-hand that family separation is an American tradition. Everything else is a mirage. And this one is also for my father.

Remembering Hiroshima & Nagasaki, August 2021

Kane ga Naru

by Yonejiro NoguchiThe bell rings

The bell rings

This is a warning!

When the warning rings,

Everyone is sleeping.

You too are sleeping.Fourth of July Release! Anthem For 1

By a stroke of luck, after weeks of waiting, an error in the label printing, some email diplomacy with the record company, a return, and relabelling, this arrives in the mail on July third. Through no planning on my part, Anthem For 1 decides to be released on the Fourth of July.

Thanks to Shi-An Costello a.k.a. coshian whose collaboration made this work possible. I gave him the raw materials and some vague guidance and he composed and recorded exactly the anthem that I wanted.

Heart Mountain Camera Club, June 5, 2021

Bill Manbo, back row, far left was a member of the Heart Mountain Camera Club. He took some of the only color photographs of camp known to exist. Once cameras were taken off the contraband list, this photography club operated openly.

Tadaima, Minidoka, June 4 2021

I arrive to find the Minidoka Visitors Center open and well attended. Ranger Kurt and Ranger Emily are leading tours but they find time to take a quick photo overlooking the baseball diamond and mess hall.

I tag along with Ranger Kurt who takes a group of high school students to the mess hall. The students imagine choosing between sitting with their parents and their friends. Most of them say that they would choose to have meals with their parents. One student says that they might sit with their parents the first couple of nights, but then they would be more likely to want to have meals with their friends. This prompts some agreement and a realization that the incarcerees would be here for thousands of meals. For me, the most poignant concept arises when Ranger Kurt talks about meals not only as a way for families to bond, but that cooking for their children is a way for parents to demonstrate their love without using words. In the context of the camps, a mess hall is less a convenient way to feed people; more a stripping away of familial routines and bonds.

From Manzanar to Minidoka to Heart Mountain June 3, 2021

Driving from Manzanar to Heart Mountain I'll be able to drop by Minidoka to say hello to Ranger Kurt and Ranger Emily. The Visitor Center at Minidoka has reopened so they are giving tours and welcoming visitors again.

On the way, I pass through Elko, Nevada as I did in my 20's. These are the same railway tracks that I travelled on decades ago when I went from Oakland to Chicago on the Zephyr.

I did not know then that these tracks were built in part by Japanese men: laborers who came to America to seek their fortune at the turn of the century after the Chinese Exclusion Act created a labor shortage.

Hiking in the Sierra Nevadas, June 2, 2021

To celebrate a successful penultimate shoot at Manzanar and to say thank you to my ancestors, I pay homage to the Manzanar Fishing Club with a hike to Lone Pine Lake on the Mount Whitney Trail.

This is not the same mountain that is behind Manzanar, but it is just a few miles south, and is part of the same range.

I start at the Mount Whitney Portal at 8,400'. The hike to the lake is well marked and maintained. It is just under 3 miles and the lake sits at 9,900', but I am not used to the thin air. I have to stop to rest every quarter mile so it is a long hike. The rewards are plentiful: continually changing views of the Owens Valley; this glassy lake, teeming with fish; a nap on a warm rock, and being able to imagine what it would be like to sneak out of camp to reclaim one's humanity for a few days in these mountains.

The Visitors Center at Manzanar, June 1 2021: Encountering Lesser Known Photographs, June 2, 2021

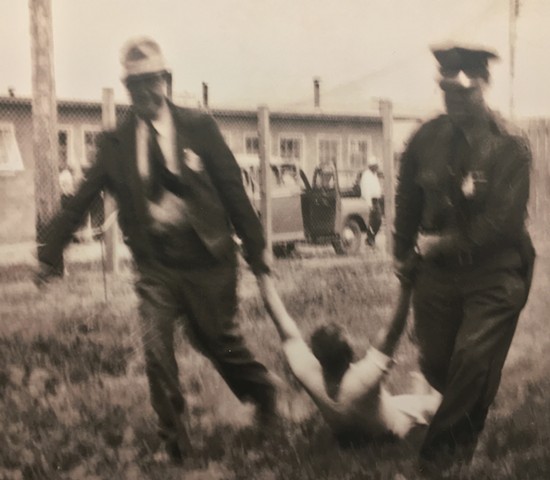

This photograph, taken at the Tulelake Segregation Center is sometimes attributed to the Civil Rights lawyer Wayne M. Collins. He spent decades defending over a thousand Japanese prisoners including Fred Korematsu, renunciants, and Japanese Peruvians who were left stateless after being abducted from their home country by the United States for the purpose of being used in prisoner exchanges.

Furusato: "This Was Our Home", May 17, 2021

On Terminal Island, near San Pedro, CA there is a memorial to what was once known colloquially as Furusato (this translates to something like "Home Sweet Home," or "old village"). Three thousand five hundred Issei and nisei lived here.

Today I visit Tuna Street, which until February 1942 was a busy commercial corridor in the Japanese fishing village. Japanese American owned businesses thrived on Tuna Street, Wharf Street, Main Street and Nagoya Street. Fishing boats operated out of the harbor at the end of Tuna Street, women worked in the canneries, children went to Walizer Elementary or took the ferry to San Pedro High School.

When the United States entered the war, the FBI arrested all of the adult Issei men who lived on Terminal Island. When Executive Order 9066 was signed, the remaining residents were given 48 hours to pack what they would carry off the island. Everything else was bulldozed.

Today Terminal Island is an industrial port and home to a low-security federal prison.

Water, May 13 2021

At the edges of Manzanar there are streams that flow from Mount Williamson around the outskirts of the camp. Prisoners used Bairs Creek as a place cool off. A dry winter this year means the creek beds are dry.

To All My Relations, A Chance Encounter, May 11 2021: Manzanar Spirit Runners

On my second day at Manzanar while visiting the cemetery I meet The Manzanar Spirit Runners. They have just completed their 29th annual run from Los Angeles to Manzanar. They invite me to join their ceremony, honoring the land and the spirit of the people who lived and died here. We spend the afternoon together, visiting the four corners of the camp’s (current) borders. The ritual concludes at the end of the day back where we started, at the cemetery.

Though our methods are different, this group of comrades and I have been on similarly motivated pilgrimages, starting from different locations, unknowingly heading towards each other for several weeks. As I listen to them reflect and give thanks at the conclusion of this, their 29th annual pilgrimage run, the importance of community bonds comes into bold relief, now that I have spent so many weeks visiting these camps alone.

To The Manzanar Spirit Runners, thank you for your generosity of spirit, omedetou, and Mitakuye-Oyasin.

Manzanar is located in the Owens Valley, home to the Paiute Peoples.

Back to Manzanar, May 10 2021

I make the trip to Manzanar from Los Angeles like so many Japanese Americans did in the spring of 1942. First, I stop at the guard tower that is pictured in Toyo Miyatake's iconic image Boys Behind Barbed Wire (see Field Notes entry below).

This is my second visit to this camp. I'm here to scout for Silence (Totem). The special use permit is pending and if it is approved I will be able to shoot at the end of the month.

I camp at the Lone Pine Campground where I have no cel reception. An advantage to spending a number of days at this location is that it allows time and space for reflection. I also end up exploring areas that I would not have otherwise.

On this visit, in addition to having a scheduled outdoor meeting with Chris Holtslander who is in charge of permitting, I run into Roger Myoraku at one of the gardens (he helps to maintain the landscaping, historical, archeological, and replica structures such as the gardens; we met here last September), and while I am sketching by the basketball court, Ranger Sarah Bone comes over to introduce herself in person (if you have read earlier field notes, you will recognize her name because she has helped me with research via email), I also have the good fortune to meet Manzanar Superintendant, Bernadette Lovato. Now that Inyo County has thankfully emerged from "red" tier into the "orange" tier, workers are gradually returning to the site. With continued health and safety efforts, the Visitors Center may reopen by the summer.

Iconic Images, May 7 2021

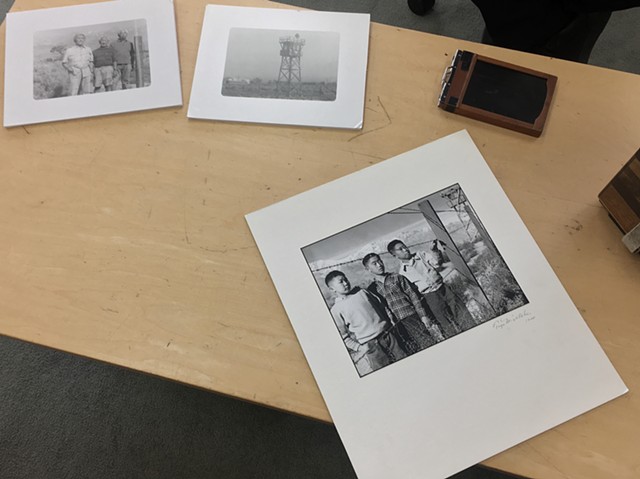

Alan Miyatake shares an original image taken by Toyo at Manzanar. He tells me a story of reuniting the men decades later at Manzanar: Mas Ooka, Bruce Sansui, and Bob Takamoto. He uses his grandfather's camera to take their photograph again (upper left corner).

In a few days, I will be at Manzanar where the same guard tower is replicated along the same fence-line.

A Visit to The Toyo Miyatake Studios, May 7 2021

A pinhole photograph of the camera that Toyo Miyatake used in Manzanar. May 7, 2021

Special thanks to Alan Miyatake for his VERY generous gift of time, hospitality and access to Toyo's camera and other artifacts.Today I visit the Toyo Miyatake Photography Studio, located in San Gabriel, about 15 minutes from its original location in Little Tokyo.

Alan Miyatake is Toyo Miyatake's grandson. He learned the family business from both his father, Archie, and from his grandfather, Toyo. Alan is now the steward of Toyo's legacy. For those readers who are unfamiliar, Toyo Miyatake created some of the iconic images made in Manzanar. He did so with the camera pictured above. You can see a short video of Alan talking about his grandfather in the JANM series, Making Waves.

Being in the presence of this minimal, carefully crafted camera is a reminder of the way in which objects hold history.

In 1942, Toyo Miyatake knows he is headed for a camp. He has to leave his photography business behind. People of Japanese descent are not allowed to have cameras at all, so he won’t be bringing a camera to Manzanar...He brings a lens and a film holder instead.

Once in the camp, a wooden box is quietly commissioned, crafted by a carpenter who laminates scrap lumber together, then sands and varnishes to make something not just functional but pleasing to hold and beautiful to look at; another equally resourceful incarceree finds cast-off plumbing fittings to make the focal length adjustable; film is smuggled in by a friend in LA who has a supply contract with the camp; a secret darkroom is set up at night in the barracks.

All of these things have to go right in order for this camera to do what it does. What it does, is capture some of the most iconic images of the incarceration. It tells the story.

Now, sitting at the Toyo Miyatake Photography Studio nearly 80 years later, talking with Alan (socially distanced, vaccinated, and masked), with Toyo’s camera on the table between us, the camera itself has a profound effect on me. It has a presence more salient than all of the photographs that I have looked at for years, and that have led me here today. It seems to hold every image that has passed through it, cast upside down by the curve of the lens, twisted into focus by the threaded pipe fittings: like a time machine activated by looking. I peer into the lens, my reflection shifts and my ancestors look back at me.

The Loss of Photographs, May 2, 2021

Los Angeles Daily News Photograph, Collection of the Japanese American Research Project, UCLA Department of Special Collections.

An FBI agent inspects photo albums in the home of a Japanese American family in Los Angeles, California, 1941.

As the FBI rushes to arrest community leaders, Japanese Americans fear that family photo albums can incriminate them: will a detail in a picture be misinterpreted as evidence of loyalty to Japan? Will a flag in the background look to an American like militarism? Some people destroy everything that links them to Japanese culture: books, records, photographs, art, dish ware, clothing. Others take their chances in order to save family heirlooms only to have them destroyed when looters ransack their storage space while they are in camp. That is if they are lucky enough to have a place to store anything. Most people only keep what they can carry by hand into camp, and they have to bring their own bed linens and towels too. Few photo albums survive the ordeal.

The Campu podcast made this episode about cameras.

Sacramento, April 25 2021

On the way from Tulelake Segregation Center back to southern California, I stop in Sacramento to see if there is any remnant of the Japantown that my Ojiichan would have known. He spent a little time in Sacramento when he arrived in the United States, preparing to establish his church in Seattle. The Tenrikyo Church Headquarters were here.

Today there is only a park where the headquarters had once been. The Japantown was bulldozed to make way for the Capitol Mall. Instead, across town, next to a freeway, there is a short city block with about four small Japanese American-owned businesses. There I find the best mochi and manju I have had since my Obaachan was alive, at Osaka-Ya.

Manzanar Virtual Pilgrimage, April 24, 2021

For the second year in a row, the Manzanar Pilgrimage goes virtual. As I watch and listen, I fill out the permit application to shoot Silence (Tarpaper Totem) at Manzanar in May.

Minidoka Shooting Day, April 20

It's windy today and it takes hours to set up. Thanks to Ranger Kurt Ikeda, Ranger Emily Teraoka, and to the National Park Service for making today's shoot possible.

Block 8 Group Photo, April 20 2021

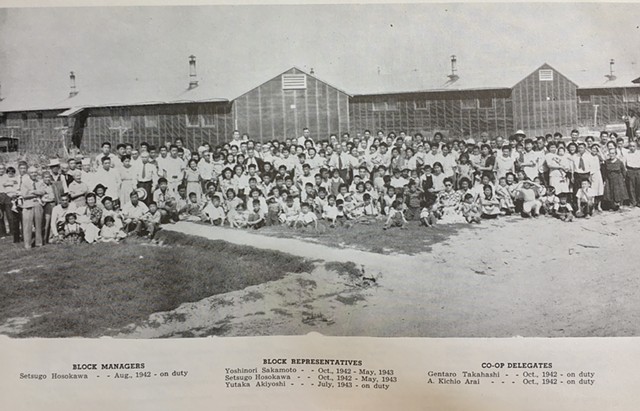

Rangers Kurt Ikeda and Emily Teraoka find my family's Block group photo in the 1942 Minidoka Interlude. I pore over the image looking for Obaachan. I think I spot her, but I'm not sure. I don't know what Dad and Michi looked like at ages 4 and 9. There are no other existing pictures from that time that I know of. It's impossible to pick them out of the crowd in this one.

Return to Minidoka, April 19 2021

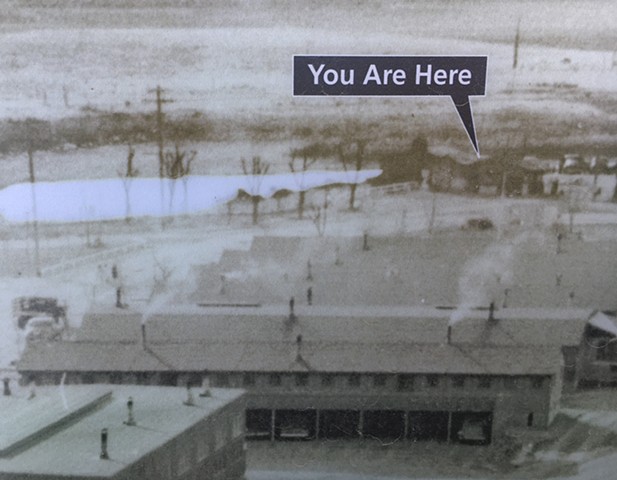

I work with Rangers Kurt Ikeda and Emily Teraoka at Minidoka to secure a permit and to make arrangements to shoot at the Minidoka National Historic Site. They both go out of their way to show me the Visitors Center and the restored buildings. They also find my family's address at the camp: Block 8, Barrack 2, Apartment C. This is located on what is now a private homestead about 3/4 of a mile away. The camp was much larger than the current historic site. It's hard to imagine a city in the desert where now there are farms.

The Japanese incarcerees are responsible for bringing agriculture to this land. It was all scrub when they arrived. They figured out how to irrigate it and make it productive farm land. When the camp closed, the government gave it all away to returning GI's and trained the new owners how to farm the land in order to give them a new start. Many of the Japanese wanted to stay, having put so much effort into the land and having nowhere else to go, but they were prohibited from participating in the homestead lottery. Only white GI's were eligible. The Japanese got $25 and a one-way train ticket to somewhere else. You might not have anywhere to go, but you can't stay here.

Topaz Hospitality, Delta, Utah, April 16 2021

I arrive at the Topaz, Utah camp after a day's drive from Red Rock Canyon in Nevada. I spend the afternoon shooting Silence (Totem) and get some rest. On day two, instead of heading straight for Provo to see an exhibition of Victoria Sambunaris large-format photography at the BYU Museum, I swing by the Topaz Museum in Delta. It remains closed due to the pandemic, so I take advantage of the online driving tour that highlights some of the repurposed barracks buildings that have been moved to Delta. Most are homes, but part of the old hospital is now a thrift store. There I meet Lee and Jodilyn. They tell me about the history of their building. Jodilyn talks about a recent remodel when they removed all of the post-war insulation and could feel how cold the building would have been for its original inhabitants.

Jodilyn puts me in touch with Jane, who runs the Topaz Museum. By afternoon Jane is taking time out of her day to fill me in on local history. She is a former high school teacher and her family ran the local newspaper so I am glad to postpone the drive to Provo. We take separate cars out to the camp. It turns out you can drive pretty fast on those dirt roads.

Even though I have already spent several hours exploring, walking just a few of the barracks blocks with Jane as a guide is a much more revealing way to see the place. Having toured with former internees she can point out details that they have shown her, and she knows where the best artifacts are. To borrow an old phrase, she knows the place like the back of her hand.

One of the highlights is this rock garden near the site of the Buddhist church. Several large rocks were curated by incarcerees who selected them for their water-collecting shapes. (The rock pictured here is about the size of a baby's car seat). These rocks came from distant foothills that surround the 31-square-mile site and would have required great effort to transport.

Imagine after a rain, the water pooling, reflecting the sky.

Special thanks to Jane Beckwith and Jodilyn Mueller for their hospitality and enthusiasm for history and their fellow humans.

Millard County, Utah is located in traditional lands of the Goshute, Paiute, and Ute peoples.

Unanswered Questions, April 12 2021

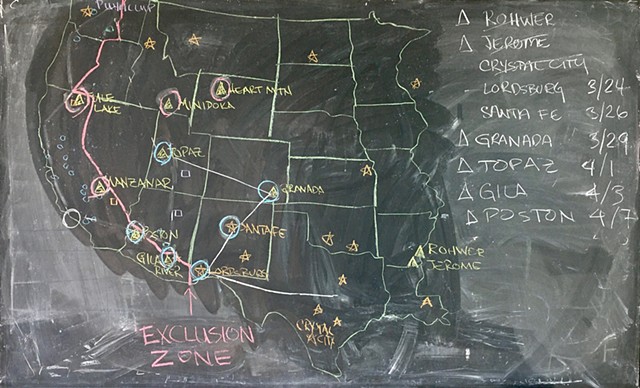

Map produced by New Trier student, based on Julie Otsuka's When The Emperor Was Divine.

I meet with Jeff Markham's high school English class to talk about the confluence of my work and their reading of Julie Otsuka's When The Emperor Was Divine, about a family who are incarcerated at Topaz.

The students look at my work and prepare thoughtful questions in advance. There is not enough time to answer all of them during class, but the questions stay with me, so I want to dedicate some time and space to answer just a few more here.

To the students: if any remain unanswered, please think of those as invitations to revisit the artworks and to look for clues, or for answers in Otsuka's book.

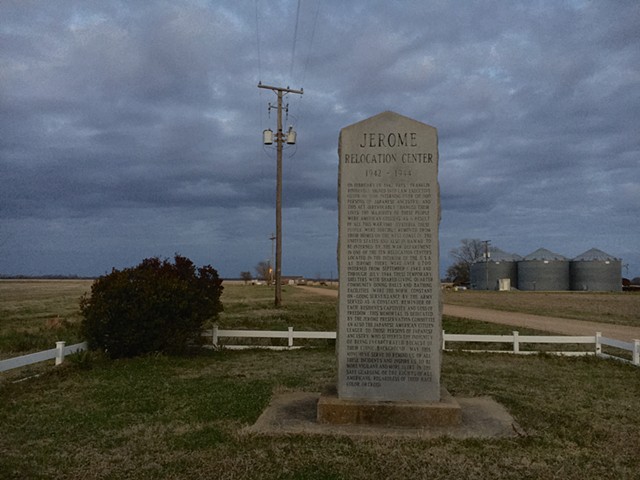

Why does it take you 45 minutes to work up the nerve to drive down Ellington Road at Jerome?

It seems absurd now, given the hospitality that the Sandlin family showed me. They were so welcoming and have since emailed me and invited me back! My experiences at privately owned properties are not always so welcoming. Sometimes I feel as though I am imposing on the people who live at these locations. I don't want to bother them if they are working, or it's dinner time. Sometimes, I think about incidences in which people have ended up in danger or worse for knocking on someone's door; I'm a stranger to these folks, and there are laws about trespassing.What is in the background of the picture at Jerome, Arkansas March 11, 2021?

There is a smokestack in the left side of the background. It was part of the camp hospital. The top of it is broken from several lightning strikes.What do the banners, blankets and nobori symbolize?

First, I like to turn any questions about symbolism back to the viewer, what do banners, and blankets symbolize to you? That is the more important answer. Without elaborating too much, I offer this list of words that I think about when I make some of these works: declarations, advertisements, encouragements, allegiances, comfort/warmth, "women's work" (handicrafts), rituals, mythology, trade and tradition.Why can't you visit the Gila River Indians?

The Gila River Indian Reservation is private property and visitors are required to request permission to visit. Normally people who have a direct connection to the camp are granted access. Currently, because Covid has gravely affected many indigenous people (particlarly elders) the Gila tribe has put a temporary restriction on visits to their land in an effort to preserve the health and safety of their tribe.Have you met other travelers doing what you are doing? Did you make any friends that you still talk to?

Normally there are annual pilgrimages to many of the camps that attract hundreds (sometimes thousands) of participants. Covid means that all of the pilgrimages were replaced by virtual events such as Tadaima! last year and this year, so I did not get to meet the people I would have otherwise. There would have been speakers and activities and memorial performances. Instead I have been almost entirely alone at these sites. Once in a while a local person acts as a guide. I have formed ongoing relationships with a few of these people: Mrs. Mollie Pressler of Lordsburg who was a high school teacher and has written a book about the Lordsburg camp led me around the area in our separate cars; Ranger Sarah Bone at Manzanar has helped me do online research and we continue to communicate by email; I've continued to communicate with the Sandlin family (Jerome, Arkansas) and hope to take them up on their invitation to return, next time with new Trier students on a field trip if possible!Is there a reason you have only two images for the Maboroshi project?

I'm not sure. Both depict sites associated with tragedies. Both are sites where my family members were incarcerated. I think that if I make more images like these, they would have to meet these same criteria.How did you come up with the categories?

I started making different works and after I had made several objects, drawings, images, etc., I played around to see what kinds of categories or themes emerged. I noticed that shadows, time travel, and memories associated with locations were especially prevalent. The works that I liked, I decided to make more of. So it was a disorganized process. I knew that Silence (Totem) would be a whole project on its own though. That one I planned by pre-visualizing, experimenting with materials, designing the sculpture and planning my route across country.What did you do with the broken pottery from Tomomi?

I haven't figured out yet how to use those pieces. I have been collecting broken glass and broken shells along the way on this trip and plan to experiment once I am back in my studio. I like to make kintsugi and I hope to be able to do this with my art students at NT next year. Do you have ideas about how to use pieces of broken pottery in a work of art?What happened to your family?

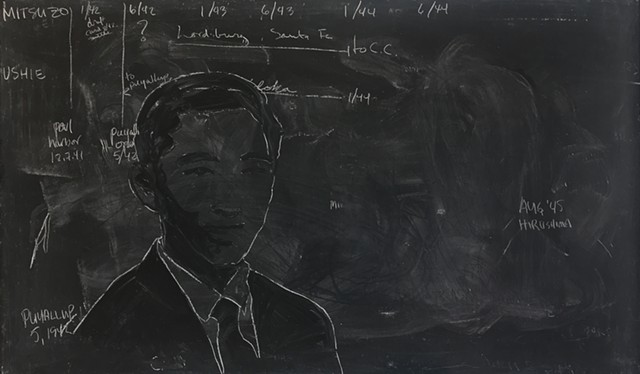

In 1941 my Ojiichan (grandfather, then age 41) was a priest. This meant that he was educated and a community leader. The FBI considered educated men to be a high-risk to national security. He was arrested quickly following the bombing of Pearl Harbor. He spent the first part of the incarceration in various high-security men's camps including the Santa Fe and Lordsburg camps. After FDR signed Executive Order 9066 in the spring of 1942, my Obaachan (grandmother, age 40), Dad (4) and Aunt Michi (8) were forcibly removed to Puyallup (a fair ground near Seattle) where they lived in livestock stalls, then they were transferred to Minidoka, Idaho in August 1942. In January 1944, Ojiichan and Obaachan were finally able to secure transfers to a "Family Internment Camp" at Crystal City, Texas so that they could be together. They spent 1944 through 1946 in the Crystal City camp. When the camps closed they had nowhere to go and no resources, so they moved to the Seabrook Farms in New Jersey. Seabrook took advantage of Japanese Americans and other war-displaced persons to fill a labor shortage. The living and working conditions were terrible: 12-hour shifts, rare days off. My grandparents had to work opposite shifts, so for 23 years they rarely saw each other or their children. They lived and worked at Seabrook until they were in their 70's. My Dad and Aunt grew up there, and eventually settled in Chicago. After my grandparents were able to leave Seabrook, they also moved to Chicago and lived with my Aunt for the rest of their lives. In Chicago, my Ojiichan was finally able to reestablish the Tenrikyo church that he was forced to abandon in Seattle. He ran it for about 10 years before retiring. He died in 1986 at the age of 86. My Obaachan died in 2007. My Dad has lived in Canada since 1971. My Aunt still lives in Chicago.Little Osaka, Los Angeles, April 12 2021

In addition to the historical Little Tokyo, Los Angeles is home to a more recently established community of Japanese businesses in the Sawtelle neighborhood (a.k.a. Little Osaka).

I finalize paperwork for the necessary general liability insurance policy that I need to shoot at Minidoka. I start planning the route north: through Topaz in Utah, to Idaho.

Next Stop, Exclusion Zone, April 7 2021

The totem will be packed up and live in the back of my car until I get the rest of the permits and insurance squared away to shoot on location at Minidoka and Manzanar. I head to Los Angeles to finish that administrative work and to explore Little Tokyo, and the Sawtelle neighborhood (Little Osaka).

Heat, Dust, More Heat, More Dust, April 2 2021

I get to the Poston memorial early, but not early enough. I scout and set up the totem but miss the best morning light.

Rather than pack everything up, I decide to stay, shoot throughout the day and take in the atmosphere. It will be twelve hours before golden hour. I'll shoot at mid day and at sunset and I'll return to do it all over again in the morning.

Spending the full day here with no distractions gives me an opportunity to read all of the historic markers at the memorial and to scavenge for broken glass for another project.

There is no shade, save for the car and a small kiosk at the entrance to the memorial. It's in the 90's. The soil here is dense and fine, like a talcum powder clay. It gets everywhere.

Tomorrow I'll be here at 5:00.

The memorial, (like the camp) is on the Colorado River Indian Tribes sovereign land.

Arizona/Tempe, April 2 2021

I stop in the Asian District in Tempe to fill my cooler and grab a socially distanced boba tea with an old friend. The greater Pheonix area has a booming Asian population. In Tempe, there is a business district that reflects this phenomenon. The Asiana Market's Covid protocols are robust and well rehearsed. I feel at home.

My friend is a foodie with a keen eye for vintage signage. He directs me to this recently closed restaurant to photograph the sign before it is swapped out for a Family Dollar or a Burger King.

Lordsburg Revisited, March 31 2021

I go back to Lordsburg to shoot Silence (Totem) on location at the Ulmoris Siding.

I decide to go back to the site of the old camp too, to pay my respects to the place where my ojiichan spent so much time and where, as my father tells it, he was changed forever.

My friend and local fixer sends a text to the property owners to let them know I'll be driving around. A reply comes back: no one is allowed on the property. No photography of the house (the former camp hospital) is allowed.

I sit in my car, outside the fence and find it ironic that the property line that once kept my ojiichan in now keeps me out.

Amache Preservation Society Museum, March 29 2021

John Hopper of the Granada High School offers to unlock the Amache Museum for me on Monday morning so that I can visit before I leave town. I have the place to myself. There is a robust collection of artifacts, art, photographs and a library. The collection continues to grow as people make contributions.

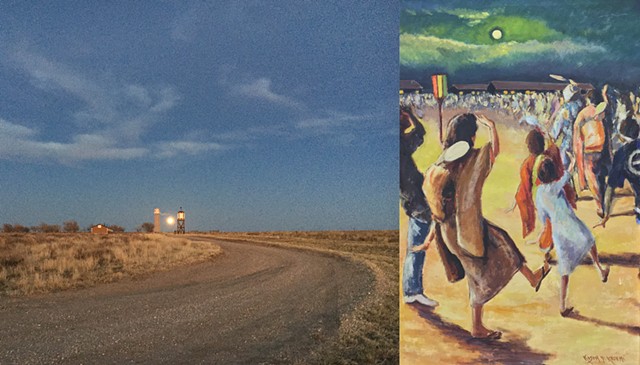

Full Moon at Amache, March 28 2021

Like my first visit to Lordsburg in October, this visit to Amache coincides with a full moon.

I only have time to catch a quick snapshot with my phone as I imagine ancestors dancing the Bon Odori under an August moon.

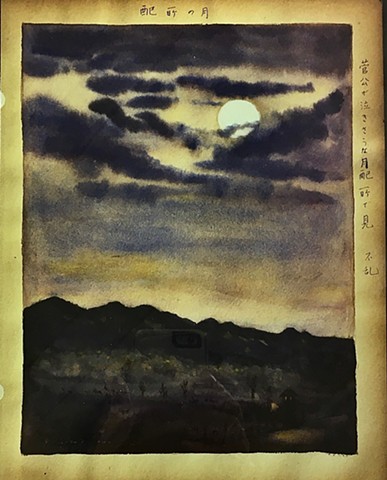

The next day at the Amache Museum (which I have all to myself thanks to Principal Hopper of Granada High School and the Amache Preservation Society), I see this painting by Kosen F. Kusumi, a former Amache incarceree.

Amache, March 26 2021

Note the sky on scouting days.

The Camp Amache water tower is faithfully replicated

Amache Cemetery, March 26 2021

At many of the camps, there are cemeteries. The cemetery at Amache is surrounded by trees and there is a memorial to the war dead. A building has been constructed around one of the older, larger memorial stones. Birds make their nests in the building but it is otherwise clean.

There are a few graves that remain at Amache. Most of the people who were interred here have been moved, but a few remain having no one to claim them. And there is this marker.

I make a note to bring water tomorrow so that I can clean the headstones.

Scouting Amache, March 26 2021

The sky is spectacular. Storm clouds are cruising off the mountains from the west and even the grassland scrub is luminous. But it's not really a shooting day, I'm just scouting and experience tells me that by the time I set up the tarpaper tomorrow, conditions will be entirely different.

I remember that while Silence (Totem) is definitely about land, it is not landscape photography. A beautiful sky is not the point.

I follow the driving tour created by the Amache Preservation Society and gravitate to one of the replica buildings.

Amache, March 26 2021

I arrive at Granada on Friday. Camp Amache is a sprawling site, mostly scrub, prickly cactus, skeletal trees and concrete building foundations. It is also cared for by the local high-school social-studies teacher and now principal, John Hopper and his students, known as the Amache Preservation Society.

The Amache Preservation Society in collaboration with the NPS and several other organizations has built replica buildings and other structures.

They have also created a driving tour map and audio guide.Before my arrival, I call the Granada High School and talk with Principal Hopper. He'll be out of town this weekend but he offers to leave the student-run museum unlocked for me on Monday morning on his way to school.

Trains, March 25 2021

I take highway 50 from Santa Fe to Camp Amache in Granada, Colorado. Highway 50 is supposed to be the loneliest road in America. It follows the historic Santa Fe Trail and runs adjacent to the Santa Fe Railway. None of the historic markers mention the people who built the tracks, including about 250 Chinese laborers.

As I drive east, I think about all of the Californians who left everything behind, traveling on these tracks to Camp Amache.

The sky changes quickly and is beautiful, depending on why you are here.

I stop to take a photo, looking back west.

White Shell Water Place, March 23 2021

I arrive in Santa Fe early on Tuesday. Santa Fe is also called by its original Tewa name, Oga Po'geh which means White Shell Water Place (Anglicized spellings vary). I scout the location of the original camp and the location of the memorial, about a mile away on a hill. The memorial is between a dog park and a gated residential road. It is close to a parking lot and will make an easy location, but there are fences and other obstructions to the view of the valley below.

The gated residential road just behind the memorial is a better location, so with tripod in hand (credibility), I flag down a car that is leaving the gated community. A few minutes later, I have the access code and an accommodating resident has sent out a text to the neighbors to let them know that I will be working on their street for the afternoon.

Ojiichan at the Santa Fe Camp, March 22 2021

Back row, fourth from left. My ojiichan at the Santa Fe DOJ camp. Very few pictures of any of my family members exist from inside the camps. Cameras were not allowed for the first several years.

I often wonder about the significance of this cohort. The writing on the back of this photograph lists names but not an affiliation.

Most of the men in the Santa Fe and Lordsburg camps were middle-aged or older, and generally intellectuals: poets, priests, teachers of things like tea ceremony, judo, and calligraphy. They were considered especially dangerous because they were educated and community leaders. This is why they were separated from their families and the rest of the community, and put in all-male high security prisons.

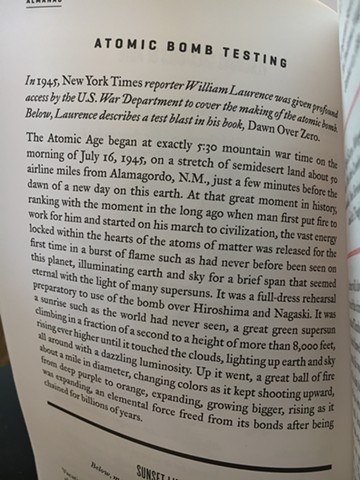

Mountain War Time, March 22 2021

On the way to New Mexico I take route 10 across Texas, also known as the Pearl Harbor Memorial Highway. I follow a map written in the lexicon of war.

All the way there I think about the US history of wars in Asian countries, and the current rise in anti-Asian hate crimes. I think about the murders of eight people, six of them Asian women, in Atlanta last week. The murderer is a white man who claims the women were a temptation that needed to be "eliminated." He did this on the anniversary of the My Lai Massacre. The coinciding date is likely just that: a coincidence, but it doesn't feel coincidental. It is a reminder that the dehumanization of Asian bodies is essential to sustain decades of war with Asian countries: the Asian body is just that, a body, not a life, something to be distrusted, defiled, caged, obliterated.

In Santa Fe I see a book on a coffee table. It is called Wildsam Field Guides: Desert Southwest American Road Trip Series. I open it at random to this page and find a bookend to Pearl Harbor; a harbinger of history's most efficient obliteration of Asian bodies.

Crystal City Family Internment Camp, March 14 2021

Crystal City is just a few miles away from Carrizo Springs. Carrizo Springs is in the news today because immigrating children are being held in the prison there. Texas is home to several detention facilities that participated in our country's family separation policy. This is why it rings hollow to me when I hear people say that we study the Japanese American concentration camps so that we won't repeat history. I seems to me that we never stopped.

The Crystal City swimming pool was built by the prisoners. It was an old irrigation reservoir, choked with weeds and water moccasins. The construction is credited to the German prisoners in Jan Jarboe's book, The Train to Crystal City. The prisoners mucked out the water hyacinth and the snakes, poured the concrete, and filled it with water so that everyone could find some respite from the heat, the boredom. It was also the site of tragedy.

I Brake for Bonsai, March 21 2021

Leaving Austin, I pull over to chat with the man who is selling these little trees. Like most of the purveyors of Japanese things here in America, he is not Japanese himself, but Korean American.

He tells me that the trees are quality bonsai, from California. I often see these roadside bonsai guys in Napa and Sonoma.

He helps me pick out the best one: a quiet companion for the trip back to the West Coast.

A Map of Returns, March 20 2021

I know that my path will be shaped by weather and other conditions. Gila may be off limits entirely due to a Covid-era moratorium on visitors.

Jerome, Arkansas, March 11 2021

It takes forty-five minutes and 3, slow passes, back and forth in the car for me to work up the nerve to turn down Ellington Farm Road, to drive past the stone monument, past the campaign signs, past the barking brown dog, to look for someone to ask for permission to work on site.

When I drive around the back of the out-buildings, I find Steven Sandlin. He puts down his work and smiles, and I can see that he knows why I am here. I'm not the first person to do this.

Steven helps me find a good spot to set up. The smokestack in the background of this image was once part of the camp hospital. The top is broken from several lightning strikes, but it has held up through several tornadoes.

Steven tells me about the land, and his family's history working for the Ellingtons who have owned the farm for decades. Soy beans and rice.

Everyone who lives and works on the farm is accustomed to people visiting the site for pilgrimage and research and art-making. Steven's father, Preston Sandlin comes out to say hello. He tells me about the photographer Masumi Hayashi who visited in the 1990's to make panoramic collages and who liked to work in solitude. Mr. Sandlin says that the white fence around the monument needs replacing; the edger has damaged it.

I work for several hours. The air smells good: a little humid. A train goes by every hour (a reminder that all camps were built in remote areas, but were accessible by train). The brown dog checks on me a few times while I work, but she is too timid even to be petted.

Jerome, Arkansas, March 10 2021

After breaking down the tarpaper monument at Rohwer, I drive to the Jerome location. This site, like the Lordsburg DOJ camp in New Mexico is on private property. I have never been there before, so I want to scout it and decide if I should stay another day in Arkansas, or move on to Texas.

It's a 40-minute drive past what will be cotton, soy bean and rice fields. It's dusk but there is a large stone monument at the side of the road that tells me I am in the right place. As I pull up to the monument, I worry that the people who live here might be tired of strangers wandering onto their property. Campaign lawn signs are at the corner of the driveway even though it is now March. The fields haven't been planted yet, it's still too early. Way down the drive, there are silos, out-buildings and a couple of homes. No lights are on, but there are parked trucks, and a big brown dog who barks at me and paces across the gravel.

I get out of the car and look at the monument. Photographer Patrick Nagatani's 1993-1995 photo essay on the camps shows the same monument on a larger concrete pad without the landscaping. Now, there is landscaping and someone has been mowing the grass.

I decide to stay at a motel instead of camp. I weigh the risks and reason with myself; I have no covid symptoms, I have plenty of clorox wipes, I can charge the camera batteries, review images made today, and decide if a reshoot at Rohwer is necessary, or if I feel like it's safe to make a cold call at Jerome. I always feel braver in the mornings.

Rohwer Revisited, March 10 2021

Today I build and photograph the tarpaper monument on location at the site of the former American concentration camp at Rohwer, Arkansas. The weather is mild but very windy so I learn how to work in those conditions. This stand of trees is just west of the cemetery and monuments to the war dead.

Today is the 10th anniversary of the Great Eastern Earthquake and Tsunami. As I work, my mind is in two places at once.

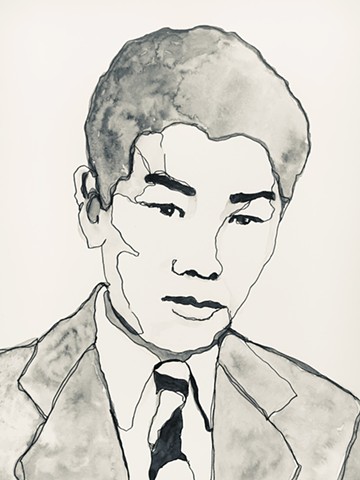

Portraits inspired by People named George, March 8 2021

I am thinking about images, rituals and identity formation, about institutions, about banality and legibility, about Japanese American guys named George.

In Seattle in the 1930's my grandparents want their American-born son to have an American name. This is the gift of the immigrant parent: a legible label to offer as compensation for the "inscrutable" face. They ask the nurse in the maternity ward to choose: something easy for Americans to say and spell. The nurse chooses "George" (my aunt gets "Marilyn"). But hard r's are difficult for my grandparents to pronounce.

My father goes by his middle name, Masatada ("Mas" for short), and in childhood by his nickname, "Mustard."

I look for other Georges in yearbook photographs from the camps. This ink and watercolor drawing is loosely copied from the yearbook photography by Toyo Miyatake. This student's name is George Nishimura, class of 1944.

The Toyo Miyatake photography studio has been sustained by subsequent generations and still makes graduation portraits.

Desert, a Collaboration with Coshian, Chicago, March 5 2021

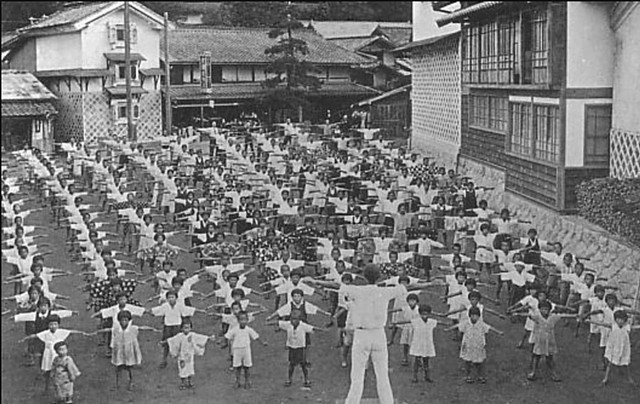

Shi-An Costello and I have been working together over the winter. Initially, I approached Shi-An with a commission to write and record a work (Anthem For 1) that is based on the music from Rajio Taiso 1. This will be pressed on vinyl later this year.

Out of the conversations that followed, Shi-An invited me to contribute found sounds to another project. Under the name, Coshian, Shi-an composed an electronic lo-fi track using a field recording that I made in Crystal City, TX at the location of my family's incarceration. This lo-fi track is called Desert. It is available on this album:Water. Desert will also comprise the b-side of the vinyl pressing of Anthem For 1.

Congratulations Shi-An, on the release of your album!

Work in Progress, February 28

I am 4 weeks (half-way) into this. It's a slow process. I have used 6 rolls of tarpaper so far and have 6 more to go.

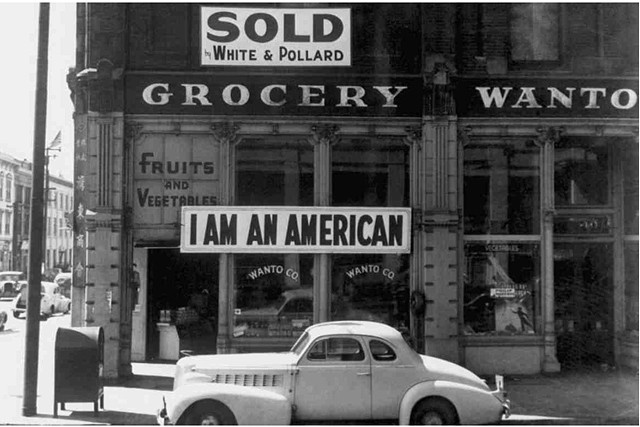

Week of Remembrance, February 15 2021

Friday, February 19 2021 is the anniversary of Executive order 9066. This week, Densho provides programming that inspires a deeper understanding of our history.

The Wanto Co. Grocery Store was owned by Tatsuro Masuda, an Oakland native. He had this sign made the day after Pearl Harbor was bombed. As a result of Executive Order 9066, Masuda and his wife were forced to abandon the store when they were incarcerated in the Gila River American concentration camp in Arizona. They never returned to the store.

Photograph by Dorothea Lange, March 1942, Oakland, CA.

Work In Progress, February 13

In Chicago for now, I begin assembling a tar-paper work to install and document at a few different locations this spring.

Tar paper is the most salient material that I think of when I conjure images of the American concentration camps: its ubiquity and utter uselessness in providing protection from the elements marks every oral history I have heard about the forced removal.

These days I'm in a race against time to prepare this work and to finish the Everything Must Go quilt before I need to get back on the road. I tear tar paper by day, and sew in the evenings. My wrists and knuckles ache and swell. Everything I do is slow, labor intensive and likely to produce repetitive-stress injuries. So a change in medium may be in my future while my hands recover.

Mustard, Austin, TX, February 5 2021

I go back through the documents that approximate a timeline of my family's separation and movements through various camps.

Having nothing to return to in Seattle when the war ends, my family resettles again, this time at Seabrook Farms, a purveyor of frozen vegetables in southern New Jersey. My grandparents work 12-hour shifts opposite one another. They pay rent to the company, and they shop at the company store. It takes them 20 years (longer?) to save enough to get out of Seabrook. My father grows up, and attends nearby Bridgeton High School.

I revisit a document that Ranger Sarah Bone at Manzanar provides in one of our many exchanges: a page from the 1954 Bridgeton High School yearbook. My father's picture appears there, and over the picture, he has written a note to someone: "Joe, Lots of luck..." He signs the note, "Mustard," the nickname he earned at Seabrook. "Mustard": clearly a bastardization of Masatada; possibly the badge of a hot temper; definitely a stubborn yellow stain.

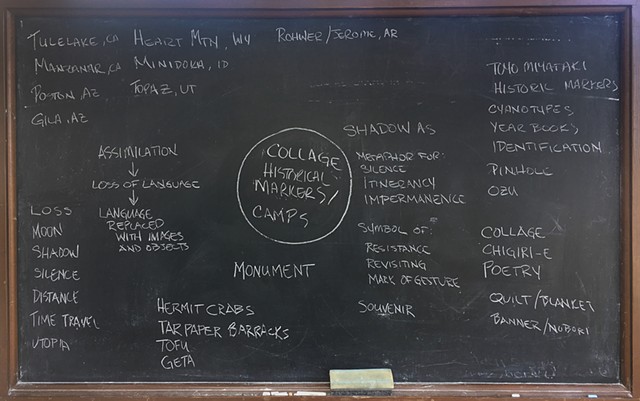

As I work at the chalkboard I listen to a podcast about the camps.

Scapegoat Cities Is made by Eric Muller. Based on granular research, Muller's narratives animate the real experiences of people in the camps.

Reading Lee Ufan to the Ancestral Homeland (now a city dump), Crystal City, TX, February 4 2021

Shot at Crystal City in the approximate location of my family's barrack, this work uses excerpts from Lee Ufan's book The Art of Encounter (Lisson Gallery, 2004). The first excerpt talks about the author's mother washing rice. A lot of Asian Americans know what this means. My mother is Irish-American but she learned from my Obaachan how to cook gohan (rice). In Japanese families, this skill usually passes down by way of the women's hands, so Japanese or not, my mother taught me how to "wash the rice."

When I think about assimilation, I think about what we lose and what we keep. Language goes, food stays. That which comes from the mouth is forbidden; that which goes into the mouth flourishes.

I can swallow my pride but I cannot speak it.

The second excerpt is about the desert, time, continuity and seeing.

School Photography, Austin, TX, February 2 2021

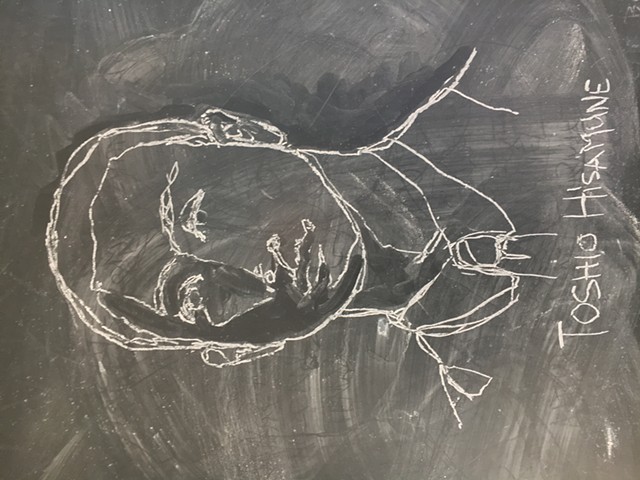

This portrait is made from the University of California's digitized copy of the Aquila, the 1944-45 yearbook from the Tulelake American concentration camp high school.

Flaneuserie, Austin, TX, February 1, 2021

Walking with no destination is a way of thinking. Add to that a camera in hand and it becomes a way of looking.

Years ago, I worked at this hotel. It didn't always look like this.

Digital pinhole photograph. Raw file, unadjusted.A Unifying Theme Emerges, Austin, TX, January 30 2021

This is the subtractive part of the process.

Study, Austin, TX, January 29 2021

I find it helpful to get things down so that I can stand back and look at what is there. This is an additive part of the process.

I learn that Korean (once Japanese) chalk is the best chalk.

No Tripod, Austin, TX, January 28 2021

I go for a walk in the hill country. I look for landscape that approximates perspectives and subjects found in late-Edo Nanga painting which was a product of influences of Southern-style Chinese literati "mountain-water" paintings of the Song dynasty.

Everything Must Go (work-in-progress), Austin, TX, January 20 2021

Today the inauguration plays in the background as I figure out a way to lay out a large-scale scallop design without the aid of a ruler. The basic framework of the design comes together fairly quickly. I begin quilting in large black stitches inspired by artist Akiko Ike's chiku-chiku sashiko (right-side detail).

Barton Springs Pool, January 14 2021

I wake up at 3:00 AM and work on the Everything Must Go quilt for a couple of hours. Sun rises at about 7:30 here so I decide to go to Barton Springs to shoot in the early light. A few people are doing laps. The morning air temperature is about 30 degrees cooler than the water (which is always around 70) and mist rises from the water. My hands are numb from the cold. I shoot for a couple of hours. There is an inkiness to the shadows, especially in this image which makes me think of the characteristics of Chinese landscape paintings: mist, trees, water.

Sound/Music Collaboration with Shi-An Costello, Chicago, IL, January 13 2021

I begin a conversation with friend and composer Shi-An Costello. I'm commissioning a work called Anthem For 1 but the project is more a collaboration than commission. We talk about the primary theme (Rajio Taiso 1), practical constraints, location-based audio, and video-game audio sampling.

The following ideas arise: patriotism, loyalty, rituals that confer belonging and reinforce emotional attachments to in-group identity; memory, nostalgia and trauma.

Here is a short article about Rajio Taiso.

Image from wikimedia.

Gigantic Slowness, January 11 2021

Back in Texas. After an 18-hour drive the everyday distractions of home begin to recede.

I read about artist Haegue Yang, I think about slowness and isolation as compelling forces in an art practice.

In a 2020 interview with Craft Council, Yang says this about the intense labor that goes into her work, "I care less about the amount of labour, and more about the time taken. The idea of taking one’s time is interesting to me, questioning if one is truly being productive or squandering these moments away. Being slow could be a form of resistance against the idea of efficiency in a neoliberal society."

Working slowly is something that I have been able to engage in recently but it is such a foreign feeling that I worried I wasn't actually working at all, even though I have been in the studio every day directly engaged in one project or another.

I realize that I had become so accustomed to equating speed and efficiency with "production" that I had almost lost my ability to recognize the value of stillness, the value of being able to think quietly for long periods of time, or to recognize the complicated ideas and work that silence and slowness yield.

A 2020 article in the New York Times says more with its title than it does with the 12 paragraphs that follow, "An Artist Whose Muse Is Loneliness: Haegue Yang seeks isolation and then mines the accompanying confusion to reflect on the nature of belonging."

This year I travel to remote sites, mostly in deserts. The pandemic has meant that I have a compelling reason to avoid people as much as possible. The sites that are National Historic Sites (such as Manzanar) have closed their visitors' centers. Tourism dwindles. The sense of loneliness and remoteness of the desert geography amplifies, but after a few hours, that disorientation gives way to something else.

Susan Stewart points out in her 1984 book of essays, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection that if “the miniature” functions to contain (for example: a photograph miniaturizes a landscape and thereby contains it), then the “gigantic” is by contrast the container; to stand in a landscape is to be contained by it. Maybe this feeling of desert solitude is related to this idea of being contained in the gigantic.

Flaneuserie, Chicago, IL, January 9 2021

In order to learn how the pinhole lens behaves, I get into the habit of carrying the pinhole camera everywhere: on routine errands, even when the light is uninspiring.

This image is taken waiting for a bus.

Shutter speed 1/20, ISO 400, RAW file, the only post-production adjustments mask dust spots.

Kokono Virtual Artist Exchange, Chicago-Kyoto, January 5 2021

I meet on-line with Sumie Sato of Kokono about once a month for a conversation about art and craft.

Before Covid, these meetings were meant to happen in person during the fall of 2020, in Japan. Instead we have managed to sustain an on-line conversation. Some of those conversations are archived on the Kokono website.

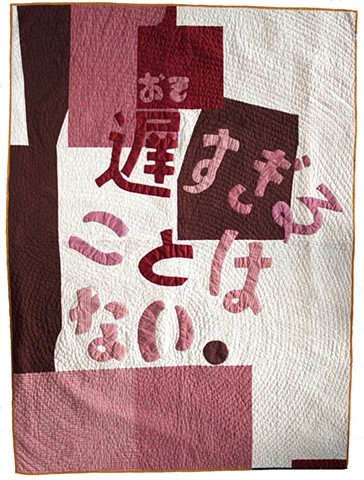

(Never) Too Late, Chicago, IL, January 5 2021

I learn how to photograph large-scale works in my apartment. Overcast daylight works best.

I completed this work this summer/fall and now I can post it.

The quilted lines will be familiar to anyone who knows Hawai'ian echo quilting. One observer also noticed a similarity to the raked lines in rock gardens like the one at Ryoan-ji, which I visited in 2019.

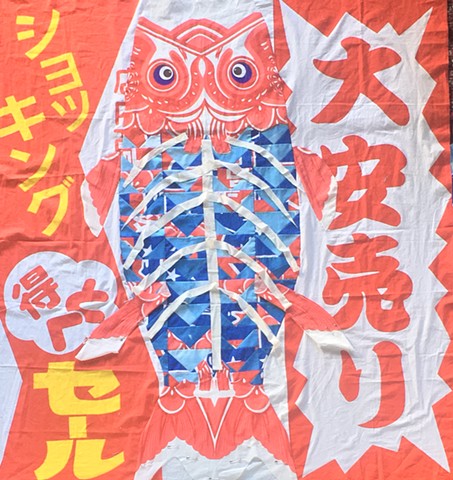

Working Title: Everything Must Go, January 1, 2021

This is an in-progress image of the textile piece that has finally begun to move forward. For weeks I had been staring at the blue and red patchwork and it just stared back at me. See the December 11 news update.

There was a minor turning point a couple of weeks ago when I made the patchwork into the body of the koi, but things really started to happen after I had a virtual studio visit with Sarah Nishiura. Via FaceTime she was able to offer suggestions: experiment with a wide variety of background options; think about the graphic qualities of the koi's head and tail; is there a way to pull the red into the background?

I dig through my collection of old advertising nobori. I find two that work aesthetically, and refer to transaction (the text says "shocking sale," and "big bargain").

With that, a resonant working title materializes and that is how I know I am on the right track.Work has been much easier since. The composition is not complete yet, but the foundation is in place.

Winter Light and Pinhole Photography, January 1 2021

When I shoot with the DSLR pinhole camera I always shoot RAW files, but I keep my playback settings in sepia since that is how the images will be printed. But the pinhole lens does something interesting to color and I like the characteristics of the unfiltered images.

This image is one of the accidental compositions that is a result of the experiments that are necessary to set up the framing in low light. It is lit by natural light only, shot at 6400 ISO, around a 4-second exposure. No adjustments have been made to the image other than minor cropping at the left side and top of the frame.

Staying In: A Pandemicene, December 23 2020

It's 48 hours after the winter solstice and the climate here in the midwestern United States now seems to reflect the condition of the global psyche. As short cold days bear down, staying inside is the natural thing to do. Disengage, hibernate, wait it out.

I work on the quilt which really means I sketch, try different fabric combinations, and wait for inspiration to strike...it doesn't.

In the mean time, the pinhole camera is a welcome distraction.

This image is the view through a closed window in my apartment of the rainy corner of Van Buren and Peoria streets.

I use a 24-second exposure and shoot at a 6400 ISO.

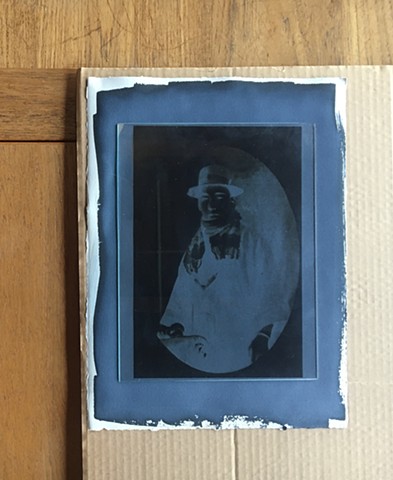

Cyanotype, Mitsuzo Funo, December 18 2020

I experiment with a variety of supports (paper, fabric). Rives BFK works well; the tan and cream varieties resist the sensitizer more than the white. The low angle of the winter sun and the overcast weather means that exposures take days instead of minutes.

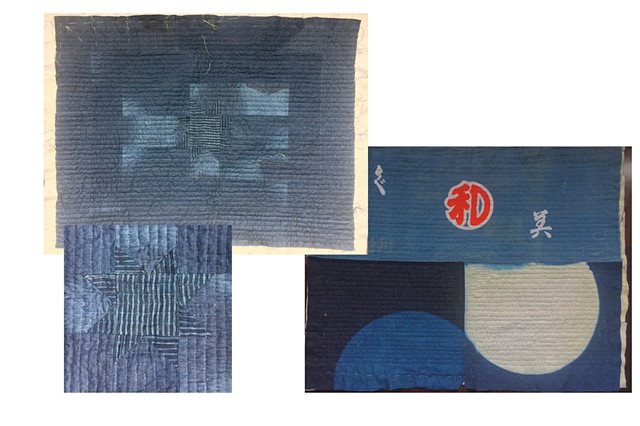

In-Progress: Quilt, Chicago, IL, December 18 2020

When it is too cold to shoot outside and while I wait for cyanotypes to expose, I work on textiles.

I take a virtual class with Sarah Nishiura.

This is made from materials acquired in the Before Times: vintage Japanese textiles from Tokyo 2019, indigo from a visit to a 2018 studio visit at Rowland and Chinami Ricketts Indigo and a denim shirt from a thrift store near Marfa, acquired on a trip in March, 2018.

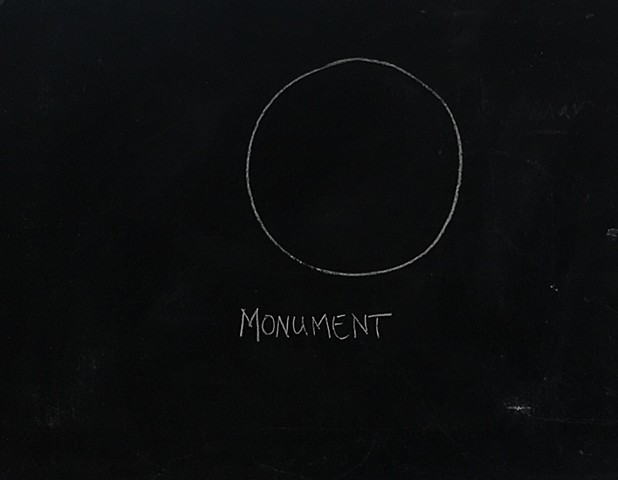

In-Progress: Monument Shadow, Chicago, IL, December 11 2020

I combine the tombstone nobori and part of the cyanotype from the Rohwer cemetery. I am not sure if I can keep going. It's the color scheme that bothers me; it's too patriotic. I can tone the cyanotype later but the colors in the nobori will resist staining and toning. I can honestly say that I hate this right now.

Pinhole Photography, Indiana Dunes, IN, December 10 2020

Prairie Grass, (DSLR Pinhole Photograph)

Today I took advantage of the unseasonably warm temperatures to spend more time outside shooting with a DSLR pinhole camera. Bright sunshine created high reflection on the display screen so image review was nearly impossible. This made the experience similar to that of using a traditional pinhole. I couldn't see through the viewfinder and I couldn't see what I had captured until I got home. Most of the images are well lit but not particularly interesting. The one I like the most is this one, which is the most "are-bure-bokeh" (rough, blurred, out-of-focus).

Self Portrait, Lake Michigan, Chicago, IL, December 7 2020

As I prepare for the next visits to the camps, I use my time in Chicago to experiment. I learn about the Japanese term are-bure-boke, which refers to a rough, blurred, out-of-focus aesthetic that was popular in the 60's and 70's in Japanese photography.

I replace the standard 55mm lens on my Canon DSLR with a pinhole lens made out of a camera-body cap.

I think about this:

I am nagged by what I think of as the ephemeral aura of certain objects: souvenirs, but also art objects. I notice this in some of my site-responsive works. They aren't the same after they are made, as they are when I make them in a specific location. The feelings and sentiments that are so tangible in situ, slowly evaporate after the works are completed: like once-vivid, then ungraspable details of a dream. In other words, I like the images when I am making them and later, I start to feel disappointed in them.

In Progress: Nobori deconstructed, Chicago, IL, December 1 2020

This nobori originally read, "Top-Quality Tombstones for Sale!"

I've been deconstructing and reconstructing this nobori since 2019. It originally read, "Quality Tombstones for sale" and I have been unable to reconcile or rework the "stars and bars" aesthetic to my satisfaction. Initially I felt compelled to deconstruct it because I thought the tombstone content felt somehow unlucky. Now I see that it might be a good companion to the cyanotype that I made in the Rohwer cemetery.In-Progress: Cyanotype, Rohwer, AR, November 19 2020

The cyanotype here is a shadow of the war monument at the cemetery on the site of the Japanese American concentration camp in Rohwer, Arkansas.

I visit on my way from Austin to Chicago. I use the morning light and the shadows cast by the monument to make the cyanotype exposure. the war monument to Nisei soldiers.

I'm not sure yet how I will use this fabric.

A package from Japan, November 20 2020

In the spring I took an online kintsugi workshop with the Sonoma Cultural Exchange, and that yielded continuing relationships with the artist, Tomomi Kamoshita and facilitator, Maki Aizawa.

Upon my return to Chicago from Austin, I find this package waiting. Tomomi has sent fragments of broken pottery that she found on Hayama Beach. I wonder how the pottery wound up in the sea. I like to think about the idea that the sea returned it to the shore and then it sailed in a boat to this continent. Sea pottery carried by sea mail.

Long Exposure for a New Moon, Cyanotype, Austin, TX, November 15 2020

I've been waking up very early, in the dark, anticipating making the most of a few more days in Austin in this tabula rasa cabin. An empty room invites ideas and leaves distractions nowhere to settle; it's the perfect artist residency space.

At night I prepare a large cyanotype sheet by ironing the creases out of it after the last light, and storing it in the only dark spot in the little building: a crawl space under the stairs. I wake up at 5:30 still not knowing what I will do with it. Over coffee I notice that there is no Moon, or a New Moon to be accurate. So I decide to make one (a Moon that is). In the dark, I set out the fabric at the threshold of the cabin, pin a double layer of thick paper discs in place and wait for the sun to rise. I spend the rest of the morning pushing shadows around so that I will get a fairly even exposure.

Blue Genie Art Industries, Austin, TX, November 13 2020

Blue Genie is one of Austin's premier fabrication studios. Their specialty is mold making and casting: the skull and dodo bird mold pictured here are made by Blue Genie artists.

I'm invited to work here for a few days, to split bamboo and make kites.

The luxury of an outdoor work space makes me think about the many different (good!) qualities of various studios. When I return to my in-home studio in Chicago, I have a cozy atmosphere to look forward to.

Thank you to Kevin and Dan for the donation of materials, space, expertise, and equipment.

Happy Friday the 13th!

Traditional Kite Making, Austin, TX, November 11 2020

Using bamboo provided by friends and colleagues at Blue Genie Art Industries, let the experiments begin! This kite is a simple, traditional Japanese and Korean design gleaned from a YouTube instructional video made by Japanese high school students (perhaps as an assignment for their English class).

As I write this I am working in a friends' guest house in Austin. Since the space is newly constructed and minimally furnished it is an ideal studio space for a makeshift, solitary artist residency in a city where I have access to resources, fellow artists, and outdoor work space. Thanks for donating the beautiful and inspiring space Kat and Rick!

Thanks also go to Kevin at Blue Genie for the materials and an outdoor space to work at his shop. Thanks to Dan M. at Blue Genie for teaching me how to split and trim bamboo. Blue Genie Art Industries has literally monumental projects under way, and they took the time to make room in their outdoor workshop to set up a socially-distant space for me to experiment as much as I wanted. I can't thank them enough.

Crystal City, TX, November 8 2020

A Failed Experiment

I drove to Crystal City, TX to capture a shadow in the location of the former Crystal City Japanese Elementary School (and current site of Benito Juarez Middle School). This is where my father went to school after being transferred to Crystal City from the Minidoka American concentration camp.After fussing around with composition and an unwieldy breeze and not enough direct contact with the fabric, I end up with little variation in values where I had hoped to see a shadow.

I order two more sheets of fabric.

Mrs. Mollie Pressler of Lordsburg, NM, October 31 2020

Mrs. Mollie Pressler is a former English teacher and art teacher, she is on the board of the Lordsburg Museum, and is also a painter. She is an avid historian and has written a book about the history of Camp Lordsburg (soon to be published).

Mrs. Pressler has been instrumental to the success of my research here in Lordsburg, New Mexico. She provided a number of hard-to-find texts and documents as well as records on my Ojiichan's arrival here in 1942. She has personally escorted me to the locations of the former camp and to other relevant sites around town, liaising with property owners, acting as both fixer and guide.

This picture of Mrs. Pressler was taken at the location where I did the majority of shooting while I was in Lordsburg.

Imprisoned People's Art and Artifacts, Lordsburg, NM, October 29 2020

Watercolor by former Lordsburg Internee c. 1943,

This watercolor painting is in the collection of the Lordsburg Museum in Lordsburg, New Mexico. Thank you to Mrs. Mollie Pressler for providing access to artifacts and archives.

The men who were imprisoned in the Santa Fe and Lordsburg, New Mexico camps were largely intellectuals: priests, and scholars. They struggled with boredom and what was widely identified as "Barbed Wire Disease," the malaise of losing one's livelihood and links to family and community. Art played an important role in tethering prisoners to the world.

Imprisoned People's Art: Camp Lordsburg, NM, October 28 2020

American Eagle Mosaic

While exploring Lordsburg, this mosaic stands out as a reminder of the role that art making played in the lives of the men who were imprisoned here. It is made of scavenged stones and concrete.

During their imprisonment the Japanese men were invited by the local YMCA to put on an ikebana demonstration for the local middle school children. They did so using local desert plants and scrap wood. The children were cautioned not to talk to the men.

In spite of suffering ongoing abuses and indignities in Camp Lordsburg, the men who were imprisoned there also found that they had time on their hands. In an effort to stay productive and to take their minds off of their worries, they made art, theater and played sports.

Poetry was also very popular in all of the camps:

I am carving the wood slowly,

At the veranda in a faint ray of sunlight on a quiet afternoon

I am 50 years old.Suirin Yoshizumi, from The Lordsburg Times issue 116

Imprisoned People's Poetry, Lordsburg, NM, October 29 2020

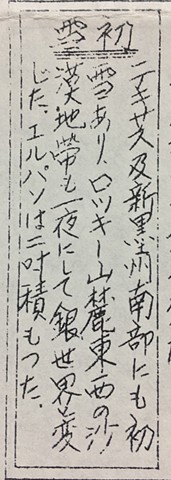

The First Snowfall

Fittingly, after the unseasonably snowy drive to Lordsburg I encounter this item in a copy of the prisoners' newsletter, The Lordsburg Times, Issue 116, January 8th, circa 1942 (from the archives of Camp Lordsburg).A translation:

The First Snowfall

It snowed for the first time in Texas and southern New Mexico. Everything was covered with snow at night from the foot of the Rocky Mountains east and west in the desert areas, It snowed about two inches at El Paso.Trans Pecos Snow Storm, Austin TX to Lordsburg NM, October 27 2020,

I spend three nights camping on increasingly cold ground in West Texas. This morning my tent is encased in ice. I break camp with cold-numbed hands and no gloves.

Now I'm relieved to spend the day in a warm car, driving from Marfa to Lordsburg even though it means heading directly into a snowstorm.

The desert transforms and the lens fogs up immediately when I pull over to take a few pictures.

This looks like a Fragrant Ash or Gregg Ash, but it's hard to tell under the snow.

Crystal City "Family Internment Camp", TX, October 21 2020

I scout locations and wait for the sun to set so that I can experiment with long-exposures. This property is now part of the Crystal City Independent School District.

This tree is growing in what was once an irrigation reservoir and makeshift swimming pool for the camp. Students sit at what was the edge of the swimming pool.

DeWitt, AR, October 14 2020

Moshi-Moshi Arkansas!

En route from the Arkansas sites, Rowher and Jerome, to Texas, I am reminded that there are vast regions of the country where there are no Japanese American communities. In these regions, when I see something like this "Moshi-Moshi Hibachi Express" sign, I get momentarily excited and then immediately melancholy.

I stop for dumplings. I learn that like many Japanese American restaurants, the Moshi-Moshi food truck is owned and operated by a Vietnamese American family.

Topaz: American Concentration Camp, Delta, UT, September 4 2020,

On the way back to Chicago from the west coast, I make a detour to visit Topaz after meeting Roger Myoraku who works at Manzanar. Roger's family was incarcerated here. It is also the setting for Julie Otsuka's novel, When The Emperor Was Divine.

Fred T. Korematsu and Mitsuye Endo were also incarcerated here. Both were involved in landmark Supreme Court cases that challenged the incarceration.

According to Densho, the Topaz site was variously, euphemistically called the "Central Utah Relocation Center," the "Abraham Relocation Authority," and "Topaz Internment Camp." It is located in the Sevier Desert and was designed to hold about 9000 people. Most of the incarcerees were from the Bay Area. Today, the Topaz site is accessible to the public. It lacks the visitors centers and replica buildings that one finds at sites such as Manzanar and Minidoka, but there are some historic markers and the concrete foundations of many of the buildings remain.

Topaz: American Concentration Camp, Delta, UT, September 4 2020

It's difficult to know if the detritus on the ground here could be dated to the 1940's or if it is evidence of recent target practice, or if this has been a dumping ground in the intervening years.

The contrast between Topaz and Manzanar is striking: the former left to decay, the latter restored. Each preserves the past in its own way.

Manzanar National Park and Historic Site, Lone Pine, CA, September 2 2020

I spend two days exploring Manzanar. Panedmic closures mean that I don't have access to the buildings, and the middle of the day is punishingly hot, so I use the early morning and evening hours to wander the grounds.

In and around the cemetery I find thousands of tsuru (paper cranes) left as offerings: a symbol of peace and healing.

My sabbatical year will be different than I had planned. Instead of being bound to a predetermined schedule, I will work intuitively. Today I am inspired to return to Manzanar, and to see more sites like it, and now I have the freedom to do so.