Historic Marker/Punctum

.

Notes on The Ethics and Aesthetics of Re-mediated Images

or The Trouble With Pictures: Identity, Consent, and Smiling in Times of Trauma

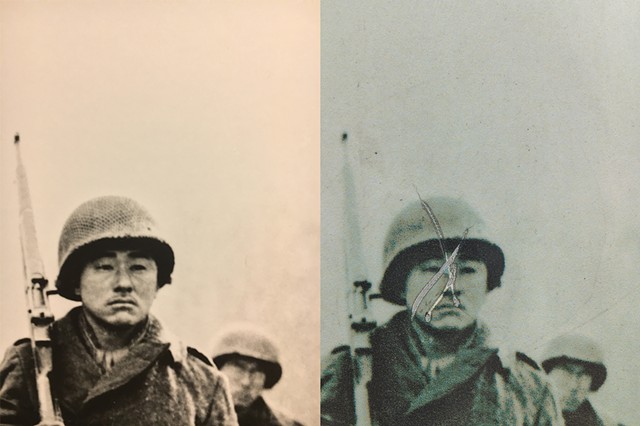

These works are photographs of photographs: appropriations and re-mediations of images from historic markers. This work is a meditation on the phenomenon of the studium vs. the punctum not only in the photograph, but in what has happened to the photograph as it is used on an historic marker.

Whenever possible, I include the name of the person pictured, credit the original photographer, and identify the source of the image.

In many cases, those identities are not available. This creates an ethical problem; how do these images work? Should the images be used at all if the photographers and the subjects cannot be identified or give their consent? Do the images fetishize the subjects?

I do not have answers to these questions, only more questions. Is my use of these images an effort to mitigate further erasure? Am I satisfying a need to remember by seeing? Is an ethically ambiguous image better than no image at all? I make the images anyway.

The Trouble With Smiling

Incarcerees’ cameras were mostly confiscated, hidden away, or otherwise left behind when they were forcibly removed to the camps, family photo albums were sometimes destroyed by their owners for fear they would be seen as evidence of loyalty to Japan. Photographs made in the camps and before the camps are scarce in many families, including my own.

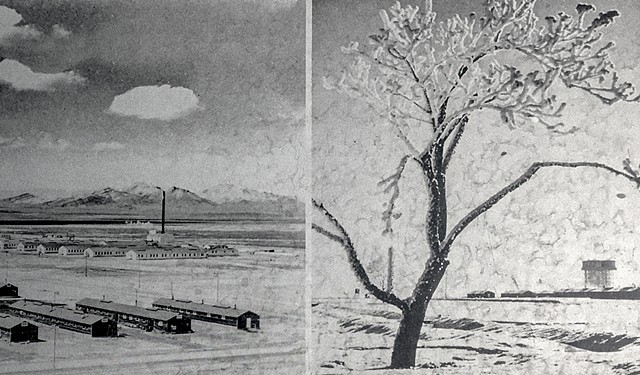

The WRA commissioned propaganda images to depict the camps without showing barbed wire, or guard towers. Two of the goals of documentary photographs commissioned by the WRA were to depict the camps as not-unpleasant places, and to prepare white Americans for the closing of the camps, when Japanese Americans would reenter the general population in large numbers. If Japanese Americans were to be resettled across the country, it would be necessary to undo some of the racist war hysteria that had been generated by early war propaganda. Friendly faces were important to both of these goals. It is not surprising that these images show incarcerees smiling.

The most iconic images of this period were made by Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange. Ansel Adams' images suggest contentment, cleanliness, compliance, loyalty, the (almost) all-American citizen. Lange's photographs are less idealized than Adams' and (not surprisingly), Lange's images were largely censored until after the war ended.

The trouble with smiles in these images is not that they exist in general. It is that they have been manipulated in order to reify the bootstraps myth that a "good" immigrant doesn't complain when they are discriminated against; and to tell an incomplete and misleading story about the American concentration camps. Life in camp according to a variety of oral histories was certainly not benign nor was it uniformly painful. The Isseis created moments of normalcy and happiness for the younger generations, so it is true that there were genuine moments of enjoyment. There were weddings in camp. There were baseball games and school dances. These events were sometimes photographed by people who had access to cameras, like Toyo Miyatake.

The important question is this: what is missing? What events escaped the camera? Within the larger injustice and illegality of the incarceration, there were suicides, extrajudicial killings, medical neglect, uprisings, work stoppages, food insecurity, family separations, and finally resettlement, sometimes in openly hostile, often dangerously racist, violent communities. We have only a few, sometimes illicitly made photographs to tell these stories. What happens when there are dozens of pictures of people smiling from trains or picking cabbages, for every one blurry picture of a man, beaten and dragged to the stockades?

For more information about cameras and the legacy of images from the camps, the Campu podcast made this episode about cameras.

![Untitled (Detail, Historic Marker [original image of Richard Kobayashi by Ansel Adams], Manzanar National Historic Site)](http://img-cache.oppcdn.com/fixed/2038/assets/T2J_RVSi0S41Bfa9.jpg)